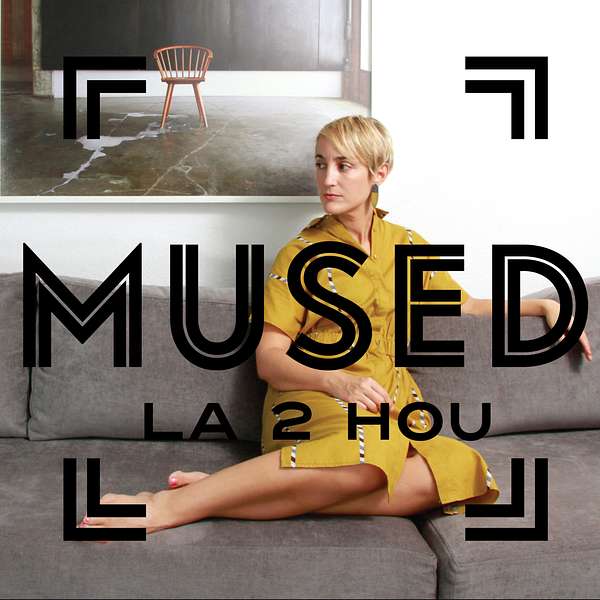

MUSED: LA 2 HOU

MUSED: LA 2 HOU

MUSED: LA 2 HOU | Sarah Sudhoff | Will You Love Me Forever

When I first moved to Houston in late 2016, I recall seeing Sarah Sudhoff at art openings, but we didn’t meet in person until February 2020 before the pandemic shut down the world. I impulsively called her one day and said, “Let’s be friends. Can...

The post MUSED Podcast: “Will You Love Me Forever” with Sarah Sudhoff appeared first on CauseConnect.

Check out more in-depth articles, stories, and photographs by Melissa Richardson Banks at www.melissarichardsonbanks.com. Learn more about CauseConnect at www.causeconnect.net.

Follow Melissa Richardson Banks on Instagram as @DowntownMuse; @MUSEDhouston, and @causeconnect.

Subscribe and listen to the MUSED: LA 2 HOU podcast on your favorite streaming platforms, including Spotify, iHeart, Apple Podcasts, and more!

Welcome to Mused LADU. I'm Melissa Richardson-Banks. Today's episode features Sarah Sudhoff from Houston, Texas. She's an artist, arts administrator, educator, curator, and I'm also proud to call her my friend. Welcome, Sarah.

SPEAKER_00:Thank you for having me,

SPEAKER_02:Melissa. It's such a pleasure to be here. Sarah has a beautiful hat on. She looks super cool and classic. That's just her look and style. She's outside of her porch and it's a beautiful day in Houston, Texas after a crazy couple of weeks of weather here. And I'm kind of sequestered and I was just telling her how pink I look. Zoom is not my favorite place to be, but she looks great. So Sarah, how is it in beautiful, sunny Houston today in your part of the world?

SPEAKER_00:It's great. I have to mention it's my favorite place to be. son's ninth birthday oh yeah so uh we're going to the zoo later today to have a socially distanced birthday party yeah last night we actually went to a drive-in movie uh which was really great so feel very fortunate that yes the weather has been spectacular here in houston and we were able to do that last night sit in the back of my subaru and then today we're going to the zoo so his birthday yes it's all about him but it's also about me too so i think a lot of people for Oh,

SPEAKER_02:I bet they do forget the mamas. I mean, you have two children. Yes,

SPEAKER_00:seven and nine.

SPEAKER_02:And this has been a crazy time during the pandemic. You are kind of doing everything here. You're cooking, cleaning, teaching, everything. becoming and being an artist, doing things. You're a chief bottle washer, they say, all of those things, right? How are you doing now with this? Not very well. Well, I do know that you've really reached out and developed a very strong support system, I believe. I mean, I know you have your artist mother group that you do, and I think that's every Sunday. Tell me a little bit about that.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, I was very fortunate early on in the pandemic to... find this group called the Artist Mother Podcast run by a woman named Kaylin. And she founded it. She's developed it. It's constantly evolving. I do not know how she has time. She's balancing being an artist, an arts administrator, a mom of three, and a wife. And she's an extraordinary friend. I can call her a friend now after almost a year of knowing her. And when we were all in lockdown and isolated and learning our new roles, no matter who we were. For me, it was learning how to be a teacher and a caregiver and my children's best friends and their security while maintaining everything else. And so like most of us, we turned very heavily to technology and online communities. And somehow I found her, I think, through Instagram or the group and started connecting and listening to artists' interviews and exhibitions. joined uh participated in a exhibition with them and then became a mentor for them and so i've been mentoring for the last um Well, I started in the fall. I guess that was my first group. And now I'm on my second group and I get to meet women from all over the country. Some of them are mothers, but you don't have to be a mother to participate. And it's just been a really great opportunity to connect and to form community and to be inspired. Obviously, my role is to inspire those that I'm mentoring, but they give me so much back and the community is so giving and welcoming that it's just been an an overwhelmingly positive experience and I am so grateful for it.

SPEAKER_02:Well, when you, when we were, you and I sat down and had a one-on-one talk before, I guess really it was right before the pandemic. It must've been maybe it's almost about a year ago now. It's probably February or maybe early March. It was definitely before lockdown because you came over because I finally just picked up the phone and said, hi, I'm Melissa. I've been lurking and looking at you for the past few years that I've been here in Houston. And I'm And I'd like to get to know you and let's be friends.

SPEAKER_01:And so I loved it. And you said, okay, I'll come over. So you came over and

SPEAKER_02:I had

SPEAKER_01:coffee.

SPEAKER_02:Yeah. And I remember sharing with you, I think, you know, if you haven't seen me, I am like this Amazon. I'm like a bull in a China shop. And I remember seeing you and now I know how strong you are, but you're just this, you're just like, you're built like a dancer, right? Or yoga. And I know you probably do yoga because we did yoga together.

SPEAKER_00:And I was a former dancer. A

SPEAKER_02:former dancer. And you have this classic beauty that I've always admired. I'm not a classic beauty, but you have these beautiful lines. Your face is just, I want to photograph it, right? And so I was a little, it's almost like asking someone for a date, even though I'm not into women, but you are someone I would date if I was into women.

SPEAKER_01:You're just gorgeous. I totally got you. Definitely heterosexual

SPEAKER_00:and definitely single. Oh,

SPEAKER_01:good. Well, maybe it's time. I

SPEAKER_02:mean, you are gorgeous, but it also smart. So that's what I loved. And I thought, you know, is she approachable? And then I realized how warm and friendly and just, and, and just intelligent and smart and so interesting. And, and I, two different, two of your projects that I saw, um, really kind of just intrigued me. Like this is her physicalness, but here is now, this is her brain. And as I got to know your brain, I was like, man, this woman's so fascinating. And it ties in with your artist mother, because one of the projects that I was really interested in was your work from, I guess it was from several years ago, but you've integrated in other ways throughout your career. But you did a project on breastfeeding. It's a project, and I think it was called Supply and Demand. And it was something because my sister and I said, oh, my God, I really want to know more because my sister and her husband, really, they developed and changed the laws in the state of Texas well before even California and other states where breastfeeding was. was you could do it legally in public and do normal things. And I really was interested in that project. So would you mind just talking about that for a few minutes? And I think that was such a fascinating project. And then how it led to it. I think you even invited my sister to be on the podcast too. So she was so thrilled about that.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah. So in 2012, my son, who is nine today, was born. And I... like many women, although I didn't know this at the time, struggled to breastfeed and struggled to produce enough milk. And so this was not something that had been shared with me. It was a lived experience, and I had a lot of anxiety around it, trying to get him to latch properly, taking enough milk, and then produce enough milk. I was also working full-time as a professor. with a really intense schedule. And so it was pumping before work, during work, after work to leave him enough milk, but I could only ever leave him just enough. There was never any extra. I did not have that freezer full of breast milk. If you've ever seen these images or gone to someone's house and you're like, oh my gosh, you have so much milk. that was never my case. And it was really heartbreaking for me and very emotional. But I didn't understand or even recognize at the time that that is such a common experience for women. And so here I am in somewhat of a silo and somewhat of a, you know, unique, what I thought was a unique experience. And I remember one of the last days that I was rocking my son, knowing that my supply was running out. And it's such a It's such a weird experience to feel your body. It's supposed to do this natural thing, and yet it can't do this thing. And you can literally feel it coming to an end. And looking at my son and going, I guess I'm going to have to feed you formula now, which is not that there's anything wrong with it, but that's not the decision or the choice I wanted to make. And now you can buy breast milk on the internet. So there's a lot more options now than there was back in 2013. So I remember, uh, sorry, 2012. And I remember looking at him and going, okay, I'm surrendering. I have to surrender. This is in order to sustain your life. I have to surrender to the fact that my body cannot do it for me anymore and, or for us. And from that kind of record, um, realization, I came up with a performance in that moment. And that performance is called surrender. So when I did birthing classes with my friend Shalina, who's an artist in San Antonio, one of the things she had me do was hold ice in my hand to try and redirect pain. So I would hold it in my hand. And if anyone knows me well enough, they know I hate cold things. I do not like cold showers or to swim in cold water. I grew up in Hawaii and Florida. I am not a cold water person. So the idea of holding ice was torturous, but it taught me something. It taught me how to understand pain and understand its purpose. So in that moment where I'm rocking my son, it all came together in some way. weird way. My brain, I think, is fascinating. Sometimes ideas come to me in a split second. And this was one of those moments, as was actually the work I've made during the pandemic. But I immediately saw the performance. I was like, I need to hold frozen breast milk and melt it with my own body. And I knew it would be donated breast milk because I didn't have any extra breast milk. And so I was able to reach out to friends who had extra or it was outdated. And I found a location, planned the performance, hired the filmmakers. did not do a trial run. And I remember when my friend, Angela, who's one, Angela and Mark, the Wally's who are great filmmakers. This is early on in their career when I can afford them. You know, she handed me the breast milk, the frozen breast milk. And I like, I screamed and she's like, Sarah, this is what you wanted. And I'm like, yes. Exactly. It is what I wanted, but I hadn't practiced, so I didn't know how cold it would be. And it was such a thrilling experience to perform. Yes, it was a private performance. And... being done in a friend of mine's house, Dolly Petit in San Antonio. And she had just redone her house. So it was actually empty in a perfect location for the shoot. And it was during this performance that I realized, one, I wanted to do a live performance. I had not done a live performance. And it was during this very excruciating 45 minutes of melting this milk while being filmed and trying to look angelic, but also thinking about how it was to breastfeed my son. And sometimes it was very intense and emotional, and sometimes it was monotonous and boring. And so, you know, in... while doing this performance i'm recognizing everything that's happening around me and to me but i'm also realizing how much it needed to be a live performance and that i wanted to return to performing in front of people which i had not done since i was a teenager as a dancer and um from that realization and that and then also watching the images in the video from that performance an entire project evolved, which was the supply and demand. And a funny side note is I was pregnant with my daughter when I did the performance. And so my two pregnancies and my two children are connected in this project, which I think is really special for me. And I began to... sort of during my pregnancy with my daughter and following her birth, I developed this project, Supply and Demand. And I was fortunate to win a Tiffany Foundation grant, which was an unrestricted$20,000 to create... Well, I could use it for anything. And I used it to live and create this project. And so it involves self-portraits, a debossed calendar of the days I was able to breastfeed and the days I wasn't able to breastfeed. It has sculptures called, plaster sculptures called milk bank, which is the amount of milk that would be consumed by a child in a day. And the molds were made from these milk collection devices that look like small, tiny gold bars, or it could be gold bars, but mine are little white milk, but they resemble gold bars. And so I was thinking about the the opportunities that we now have to purchase milk, whatever it is, whether it be formula or actual breast milk. And then I did the live performance that was actually, I had done the live performance first in Houston, Surrender at Nicole Longnecker Gallery in 2013. And then I was able to do the performance again in San Antonio at French and Michigan Gallery. And that was such an extraordinary experience to have my work up and then to sit there in front of friends and sit there in front of some of the audience I didn't know. And I didn't make eye contact with anyone, but it was really exciting to experience them experiencing me and watching the milk haphazardly flow onto the ground. And so it was this invisible labor that mothers go through. You feed your child, but you don't see it, right? You just know that they're consuming milk and you hope that they're consuming enough. But the act of melting milk with my body and watching it flow out onto the ground was such an extraordinary experience to think that this is what mothers all over the world are doing, yet no one can really see it. And to have a visual representation of what that looked like was so fascinating to me. And it also, at the same time, was heartbreaking that I never had enough milk to do that. I could have never made enough milk to do this performance myself, even if I wanted to. And so that some women, they're just, That's how their bodies are made. They're able to produce enough milk and extra milk and they donate milk, which I think is fantastic. And I have a relationship with the Mother's Milk Bake in Austin. They've allowed me to come photograph there. One of their beakers is actually in my project. And then that beaker is the silhouette that made the calendar called Failure of the Ordinary. And one of the most extraordinary or really special moments in that project is I invited a group of midwives and doulas to French and Michigan gallery. And I had my daughter with me. She was a couple months old and had her straddled on my hip. And I'm giving this talk in the gallery. And both my pregnancies were kind of difficult. My first pregnancy, I had a placenta previa, which meant I could not have a natural childbirth. And I couldn't do certain activities and sports. And I had to be very careful not to bleed out. Luckily, in the end, I was able to have a natural delivery. But then when I was pregnant with my daughter, I was high risk. because I was over 35 and I could not give birth at a birthing center, which was really what I had wanted to do. But I ended up having doulas and midwives, but in a hospital setting. And so it was really special for me to have these doulas and midwives to see my work because that was really important to me. And one of the midwives admitted to me that in seeing my self-portrait called ill-equipped, which I'm standing there, you don't see my head and I've got these milk collection devices covering my breasts. And one of my breasts is noticeably larger than the other breast and able to produce a lot more milk. And that was how it was with my first child and my second child. Again, here was a situation where I thought something was wrong with me. I thought that I was literally ill-equipped.

SPEAKER_03:Not

SPEAKER_00:knowing- that that was normal.

SPEAKER_02:Yeah.

SPEAKER_00:Completely normal.

SPEAKER_02:Well, what I love about you is the fact that you truly are a photojournalist that executes your expression in a variety of art media. And I think what's interesting to me about you is that you put yourself out there too. I mean, you mentioned that performance art really wasn't your... medium, if you will, at that point, you had been a dancer, but not in terms of your expression of the story. And I guess when I first heard of you before I even saw you and spotted you out, I knew of you as a photographer. And then again, like, like a lot of us in the creative fields, there's just so many layers. And I What really attracted me, again, as I peel back the layers of you, is the fact that you're a dancer, you're an artist, you're a photographer, you mix media, you're three-dimensional, you do installation-based. But all of that came about really from... You were just, I mean, you were, you were a, you grew up in a home of scientists. I think, was it, tell me a little bit about your upbringing. And I think you also, didn't you toy with going into the military for a while? I mean, there's all, tell that journey because I, I still kind of trying to figure out the idea of this, you know, young dancer, but who also aspired to be a scientist and then how really these worlds have come together now,

SPEAKER_00:now as a

SPEAKER_02:mom, as an

SPEAKER_00:artist.

UNKNOWN:Yeah.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, it's like really interesting to sort of like think about and I don't know how long winded this will be, but hopefully it'll make sense. But growing up, I come from a military family. My father and grandfather were both Navy pilots and my grandmother was actually a wave. She was in the Navy. And so I was expected to join the military. However, in middle school and high school, I was drawn to dance and piano and music. I did have an early on interest in being a physician or a doctor. I used to love trauma in the ER. That was like one of my favorite shows. And I would get in trouble at school because I would talk about the things that I saw, some of them gory details or some of them sexual things, but it was all from a scientific perspective. But I was so fascinated as a fifth grader, but those conversations weren't permitted at my private school. And so I would get constantly pulled out and told not to talk about these natural, normal, everyday occurrences. But as a fifth grader, it was inappropriate. Although, anyway.

SPEAKER_02:I'm going to jump in right there for a second because that was a pivotal point in my life in the fifth grade as well. There's a reason why that I'm not an artist today because I was an artist up until the fifth grade and I was pulled into the principal's office because they thought that my, well, it was advanced, my figurative drawing. But for some reason, I guess I was obsessed with breasts because I had enlarged breasts on women and they thought that was inappropriate. So I was told, they brought my parents in and they said, she can't, she's not able to, we don't want her to draw anymore. And I quit. Yeah. Because I was forced to, but anyways, so it's important what happens during those, those, those early ages. My mother now is an artist and she's horrified that she allowed that to happen because she became an artist about 10 years ago. So it's important what we do with our kids and what you learn at those ages. So go ahead from fifth grade.

SPEAKER_00:So. And I didn't really... I don't think I grasped at the time what my interest was or understood where it was coming from. But it was just an interest I had. Everyone was watching or playing video games or whatever they were doing. But this happened to be my interest. And then I remember sometime in middle school... Oh, actually, yeah. So that was elementary. Sometime in middle school, I remember telling someone I wanted to be a surgeon. And they said, Oh, you're a female. You'll never make it. And sadly... Sadly, that interest of mine was not encouraged. My Cuban grandfather was a surgeon and my Cuban grandmother was a scrub nurse in Cuba before coming to the United States. So I do have some physicians in my family. And then I had the military upbringing in my family. And it was in... I would say elementary or middle school that I first picked up a camera. We were moving all the time. And so by the time I got comfortable in a place or in a space, we were moving again. And I had no real record. I had my family's record, but I didn't have my own record. So I remember in middle school and in high school taking a lot of pictures. That was sort of like an outlet for me. I stopped dancing in high school. I started playing soccer. And then I was at the top of my class. I think I was like number four or maybe six in a class of 400. I was kind of nerdy. I was both the nerd, the athlete, and the goth girl all combined in one somehow. I was just nerd.

SPEAKER_02:I was just nerd. You got me at

SPEAKER_01:goth in the other, but now I was a nerd.

SPEAKER_00:I was all of it rolled into one. And I remember having this really great science teacher, Ms. Goggins. I don't know if she's still out there, but I remember I wasn't doing really well in her class. I wanted to make all A's and I think I had like an A minus or a B. And she's like, Sarah, if you want to be a scientist and a doctor or physician or whatever you want to do, you have to stay in this class, even if you don't make the grade. You have to learn this information. And she really pushed me to persevere. And I don't even know what I ended up making, but I really loved the fact that she challenged me to, you know, that it wasn't always about making the grade. It was about the knowledge. And come near graduation, I remember meeting with a military recruiter and thinking, okay, maybe I'll be a photographer in the military. That seems plausible. And then thinking, is this really the direction I want to go? I'm expected to go here, but do I fit here? And I decided against it. And I decided to go to college instead. And And interestingly enough, I actually went to university to study astronomy. I had grown up in Florida, near Cape Canaveral. And my father had always wanted to work for NASA. And that was a dream of mine. I used to get to watch the shuttles launch, not from Cape Canaveral, but from my street. Oh my

SPEAKER_02:God, what an experience.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, I could see them, you know, shoot off into the sky. And I thought how fascinating and how interesting it would be to be part of that legacy. and that experience. And so I actually was accepted to Vassar and a couple of other colleges to study astronomy, but ended up going to UT for financial reasons. And after my freshman year, I switched gears. It's not that I didn't love science and the stars and space and travel and physics and calculus. But there was something about it that didn't fit my personality quite. It wasn't quite the right fit. And I spoke to someone in the journalism department at the University of Texas, Rick Williams, who is the head of the program, who sadly passed away two years ago. But he welcomed me with open arms into that program. Yeah, he really shifted my life. Wow.

SPEAKER_02:So it sounds like you've been, you stayed in touch with him. I mean, or at least he was a critical part of your life. And you obviously know that he sadly passed away a few years ago. So.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, he founded the Texas Photographic Society, which I was the executive director of for a year. Oh,

SPEAKER_01:heart, heart. Oh my God. So it's full circle.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, yeah. So I, you know, in 2009, I started a photo nonprofit in Austin called the Austin Center for Photography. We had, I, you know, we didn't have a brick and mortar space, but we had, it was called the Icons of Photography Lecture Series. And it was a really... fantastic just uh experience and exposure to bring these uh photographers to austin and um I don't know where I'm going with that. Sorry. Oh, well, just, you know, my interest in being part of photographic nonprofits after leaving New York and coming back to Texas, I was like, there are not enough organizations and galleries and spaces to connect and places to meet these fantastic artists. And so, you know, I was really, really interested in helping change that, the landscape of that in Texas. And so a couple years ago, or actually several years ago, I was a board member for the Texas Photographic Society. And then in 2019, I was their executive director. And yes, it felt like full circle, knowing that Rick was the reason I became a photographer and really embraced me. And here I was running the organization that he founded. Wow. It was really wonderful.

SPEAKER_02:Wow.

SPEAKER_00:That's skipping a lot of years. Sorry.

SPEAKER_02:Well, I want to go and tap into the military aspect of your life. My... The second body of work that really intrigued me when I first learned about you and that I saw in person was your... I think it was... Was it called Point of Origin or was it Mechanics in Flight when you did the Cindy Lissica show? Did you have a working title?

SPEAKER_00:It was always Point of Origin. Mechanics of Flight is the name of the kites themselves.

SPEAKER_02:Okay. Okay. The actual installation piece that you have in there. Okay. Because I remember stepping into that gallery and... First, I was just intrigued because at first you see this amazing installation and then the whole space you see, I guess, were those prints that were textile threads, sculptural, there were some photographic

SPEAKER_00:self-portraits. Well, so the first... installation at Cindy's was the three kites, then debossed patterns on the wall or printed debossed patterns. And then the sound installation was me breathing at four different rates. And then the one in Austin last year had the self-portraits, the kinetic sculpture, sound pieces, and other photographs as well. So yeah, the first iteration was much more minimal.

SPEAKER_02:And I think, so, but when I, when I really connected with that the installation in the show, it hit me because my father built helicopters. You know, he was with a Rad Mac and he, um, developed this floating warship during Vietnam war. It was a, it was a, it was really for helicopters to come down and then they would be at sea and they would be, you know, all the repair work that would need to be done during wartime and helicopters just meant a lot to me. And my, I had just lost my father, I think right before, maybe a maybe months before your show. And it was always this part of my childhood with my father. And so I immediately connected to what you were saying. And then I realized a lot more about the show. So share about Point of Origin and how you brought this piece together. Because I just think it's just an amazing story about- So Point of Origin is, it's a multidisciplinary series and it includes the sounds of aviation, of course, military planes and helicopters. And what inspired you to do this? What did you, why?

SPEAKER_00:So I lived in San Antonio for seven years and one of the places I lived, I was under the air emergency helicopter system flight route from one of the downtown hospitals to the medical center in San Antonio, which is sort of like on the northwest side of San Antonio. And so I could hear the helicopters flying over me all the time, and I knew what they were. And then because San Antonio is such a military town, I could also hear the military planes, you know, the Air Force jets and the larger cargo. My dad would be so unimpressed that I don't remember the names of these things. But the ones that you can drive vehicles onto, like the back hatch opens up and they look like a whale, a whale in the sky, you know, you know, that one. I don't know what they're called. And so it was this really interesting visual auditory experience for me to keep both the medical chopper and the military combined in one. And I didn't think anything more about it, but it was just something that I was aware of. And I knew it was interesting to me. I didn't know why it was interesting, except the fact that I'd been interested in medicine and that I came from a military background. Did I ever intend to make a project about it? No. When I moved back to Houston, because this is my third time to live in Houston, and I started noticing all the red helicopters here. And of course, being a curious former photojournalist, as you do, you research. And I came across Memorial Hermann. I came across Life Flight. I read about the history of Red Duke, that it was the first... entity of its kind in Texas, and that it is the busiest helipad in the country to date. And that no one had done a project about it. Yes, Lifetime had done a series, Drama in the ER. You know, the show that I used to watch in fifth grade and get in trouble for, but that they had done a special episode on Memorial Hermann's Life Flight. So talk about another full circle coming around.

UNKNOWN:Yeah.

SPEAKER_01:Oh my gosh.

SPEAKER_00:And I had the opportunity to apply for a grant through the Houston Arts Alliance. And this would have been in 2018, 2017, I think it was 2017. I was awarded a large grant to make a project on Memorial Hermann's Life Flight. And it took me over a year to get access to the VP of Life Flight. I tried through my mom, who works for the health department here in Houston, marketing. I tried through... a doctor friend of mine who's an ER doctor at the hospital. It was like any avenue and all avenues I was exploring and constant emails, phone calls. And finally, after a year, they invited me in to give a presentation. And so I'd started this project and built a website that was going to collect stories from the public. Because if you go on their Facebook page, they've got all these incredible... journeys and testimonials of people that were saved and how, you know, even if they weren't saved, they were, their family member was given this extraordinary opportunity, right? And at life. And by being in the helicopter versus an ambulance or other means of getting to the hospital. And unfortunately, that project was shut down by Memorial Hermann. They, for HIPAA reasons, they could not support it. And they said, well, what else do you want to do? And I told them, I want your flight logs. And that really stemmed from my dad because my dad was a pilot and I would see his flight logs. Where was he going? What was he doing? And so he was in the Navy for 15, 20 years. And then he was a customs pilot. And often I didn't know where he was going until he got back because there's like these secret drug bust missions and things like that. And so, yeah, he was flying to Ecuador and Peru and Brazil chasing drug lords in the air. Wow. So I wouldn't know. Yeah, I wouldn't know where he was, nor when he was getting back until he was back. And this is sort of a side note, but my dad would fly over my school when he would get back. Oh, I love that. Oh my God. I would see his plane because it was a very unique plane. It was a P3 with a rotor dome on top. It was called the AWACS. That one I know the name of, but the AWACS would fly over. And I'm like, oh, there's my dad. He's back from some undetermined destination. Oh, my

SPEAKER_01:God. I love

SPEAKER_00:that. So, you know, this idea of a flight log was really interesting to me. Where were they going? What were they doing? When were they coming back? And so when Memorial Hermann asked, well, what do you want? I said, I want the flight logs. I want to know where your helicopter started out. I want to know where they picked up a patient. And I want to know where they delivered a patient. And it took me a year to get that. I got one month. of flight logs, which is about 330 flights and for five bases that support the Houston area. I was able to meet with some of the crews, talk to the pilots. I did a lot of research and a lot of interviewing. Some of that showed up in the work. Some of it just informed the work and just allowed me to understand the dynamics of working or being a life flight pilot or nurse or tech. Um, maybe someday the rest of it will, will filter in, but, um, I, I just try and dive in as deep as I can and become as familiar with the subject as, as one can from the outside. Um, when I'm working on a project. And then again, I think that stems from my photojournalism background. Thank you, Rick Williams. And, um, And so, you know, I got these flight logs and I had a friend of mine here, David Richmond, who's helped me on a lot of projects. And I said, okay, I've got these numbers. Can you help me make patterns out of them? And we made these patterns and they were PDFs. And I'm flicking through the patterns, looking at them really quickly. And as I'm flicking on my computer, I'm like, oh, they move. They need to move. The patterns need to move. And then that's where the sculptures came from. It was not, oh, I want to make sculptures off the patterns or off the flight logs. I knew I wanted the flight logs. I wanted to see what the flight logs look like as a pattern. And then when I flipped through the patterns, they became a sculpture.

SPEAKER_02:Oh, my God. You've shared part of this with me before and Even just, I could hear it over and I've just, I always learn so much from you and how you do this. It's just so interesting to me how you just kind of take a deep dive. You really thoroughly research it. I love that fact that you said it informs your work and I'm just, I love it. And I'm bummed that I didn't see it when it was expanded in Austin. It was Gray Duck Gallery, right? Yeah,

SPEAKER_00:Gray Duck Gallery,

SPEAKER_02:yeah. But your website has a lot of documentation, so if people want to see a little bit more about it, it's pretty thorough what you have on there. Yeah,

SPEAKER_00:there's a video walkthrough of the gallery, which I was really happy to have that. That was something that Glass Tire did last summer for all the artists whose exhibitions were canceled or closed, they said. Send us a five minute video. And so we were able to put that together. And so it's really great that I've got that expanded documentation of the show because I think seeing it and it still images one experience and then be able to watch this walkthrough and how all the pieces are laid out in relation to one another is, you know, it's on a whole nother level. So.

SPEAKER_02:I love Glass Tire. Thanks, Glass Tire. That was so awesome. It really helped me this year to be able to see a lot of the openings and stuff that I missed. So you've really been busy during this time of coronavirus and COVID. And there are a couple of things. I know you were just recently featured in, I think, Southwest Contemporary Art Magazine and their Bodies and Boundaries issue. And I thought, I remember seeing an image of that. I think it was called 60 Pounds of Pressure. Can you talk a little bit about the work that was just featured in the magazine? Because I was really blown away by that.

SPEAKER_00:Sure. So I would say other places in the country were starting to lock down. My show earlier than Texas, my show opened at Grey Duck March 6th and was closed the week after. I remember taking my children on a remote spring break And then coming home and really realizing what was happening in the world and that they were not going back to school. I was not going back outside, at least for a period of time that. our domestic space was going to be our entire space. And reaching out to friends, especially family and friends in New York, which was at that time, if you remember, March 2020, was just the hotbed. And I had so many friends and family there and was just terrified. Here, at least in Texas, and specifically in Houston, we're a little bit more separated. And we've got side yards or backyards or access to green space without having to bump and rub shoulders. And just seeing the images coming out of New York was just horrendous. And so So heartbreaking. And I remember in March learning about a young nurse in Georgia. She was one of the first frontline workers to succumb to the illness. And she was found dead at home with her four-year-old by her side. And as a single mother, I could comprehend it. I was like, if I get sick... you know, who's going to take care of me because I don't want to expose anybody else. And then if I die, how long does it take for someone to find me? And how long do my children have to sit with me? And what does that do to them long-term? And, um, I, it was just a really unsettling and horrific and all consuming experience to happen. Um, and I, I, asked my children to lie on me. I told them I wanted to do this performance because I felt such burden and such weight and such responsibility all at once and fear and anxiety. It was like all these emotions rolling around inside my chest and I could feel it. And I wanted to somehow document it and share it Not necessarily with the world, but just get it out of me. It was so heavy. And this is one of those moments that it didn't take a year to get access. I read this news. I had this immediate visceral response to that information, even though I didn't know this woman or her family or anything else about her. But just the fact that I was a single mother, she was a single mother. She was doing her job and she died. And... So I asked my two kids if they would lay on me so I could do this portrait. And of course I asked, I told them I wanted to be naked because I wanted to show my body with their body and the impact of their body on my body and the impact of their weight on me and how I was holding them up and holding them together and holding us all together and balancing it all. And even in March, I didn't really know what that meant yet. Right now, a year later, I really understand what that means. everything that I've had to do. But in that moment, I only had like a preview or a glimpse of what the next, you know, year would look like. And because I wanted to be naked, my children said, no, mom. And, you know, it's good for them standing up for themselves and, you know, setting their own boundaries. But I said, okay, could we please do it with your clothes on just so I could know what it feels like? And, you know, trying to research, okay, what would this experience actually feel like? And so my son laid on me first because he was first and then my daughter laid on top of him and I could barely breathe. And it was difficult to balance them on my chest while I was breathing. And in that moment, it is so weird the way sometimes art unfolds or ideas unfold. In that moment, I was like, oh yeah, I've got bricks in my side yard that I pulled up to make a play space for you guys. I'm going to go get the bricks.

SPEAKER_01:Wow.

SPEAKER_00:And then we placed, I had a friend that was there and we placed brick after brick on my chest until I couldn't take anymore. And I could still, well, that I could take and still breathe, right? Of course, I probably could have taken more weight, but I wouldn't have been able to breathe. And so it's like finding that sweet spot, that balance of the pressure, but still being able to, still being able to maintain life or still be able to maintain a breathing rhythm. And so we placed the bricks on my chest. We had already had the camera set up. And we snapped a few images. We shot a very short video. And that was it. And then it was done. And that all happened in one day. From finding out the information about this woman to... telling my kids about it, to putting the bricks on me, to having these images and this performance that I started to share because... institutions, the Pandemic Archive, which was actually started by graduate students at Parsons, where I'd gone to school. And so several organizations like that were putting out calls for artists to share the work that they were creating. And that's really the only reason it was seen is because people were asking. And so I happened to have this Well, I didn't even think of it as a project right then. It was more of like therapy and an outlet. And I shared it and it just evolved and blew up from there. And people got really excited about it. And then I did the performance in July live for the Pandemic Archive over Zoom, which was a really weird experience. And I don't know that I want to do another Zoom performance because I've realized how important the audience is to supporting me during that. doing a live performance and how much I get out of the audience watching me. I feed off their energy just as much as they feed off mine. And I'm fine to do performances to be recorded, to be seen in a gallery as a video. But in terms of a live experience, I want there to be an audience. And so... And then I redid the performance. I did a 30-minute version of it because it went to an exhibition in Tennessee. And then luckily, I had that version to share with the Blaffer Museum, who asked this fall if they could exhibit it as part of their current exhibition, Carriers, the Body as a Site of Danger and Desire.

SPEAKER_02:Okay, so that's the one that's actually up there now. And you have some of your prints. I think it leads to... Will You Hug Me Forever, which is the work that really hit me as well. And that body of work. And those two bodies of work, that's what's on view currently at the Blaffer Art Museum in Houston, Texas. Can you talk about that? Because the Will You Hug Me Forever just... blew me away because obviously we're all living through this COVID-19 pandemic and we're, we're dealing with having to wear a mask. And obviously here in Texas, things are changing next week. Supposedly it's the mask mandate is gone, but I think we're all struggling with the fact that I think people that wore masks before are going to wear a mask after until we're safe and people who didn't do it before are not going to do it anyway. So, um, Share about, will you hug me forever? Because I, and again, the imagery is on your website. It's also on your Instagram. And of course I'm really wanting to go and see it live before it closes March 14th, 2021.

SPEAKER_00:So 60 pounds of pressure was a performance that was documented through images and video. And I, I unfortunately had family die from COVID in New York. So they were extended family. It was my dad's wife's sister and brother. Some friends of mine in New York, close friends also had COVID, but luckily recovered. One of my good girlfriends and her son. And so here I am in Texas, relatively safe. And I've got family and friends in New York who are being exposed and dying. And then I've got friends and family who are physicians all over the country trying to save people. And in one way, I felt so protected in my isolation, but so helpless in my isolation. And I wanted some... I wanted to mark that sort of feeling and recognize what was happening to so many people in a different way than the bricks, because it was a... Although that piece was shot only a couple of weeks after 60 pounds of pressure, but in that short of time, the world was changing so quickly. And now, not only... were we in lockdown, but now we were losing people and we knew. And every day the New York times was mentioning, you know, who was dying and printing all the dead names. And so, you know, it was so impactful to me, even though, like I said, I was relatively safe. I lived through nine 11 in New York and I should have been right there. My boyfriend at the time was, It was a few blocks away. I would have run to the towers to photograph as a photojournalist. I was working at Time Magazine. And I, like many others, have survivor's guilt. And I think, in a way, I was having a similar reaction to COVID that I wasn't in New York. My friends were. They were getting COVID. Other people I knew were getting COVID and dying. And in some way, I think, and I'm sure I'm not alone in this, having survivor's guilt. that I wasn't on the front lines and so many people were. And I wanted a way to honor, at least in the way that I could, right? I couldn't be out there on the front lines. I had two children to take care of, but how could I honor those that were on the front lines and those who were living, giving up their life to save others? and to honor my friends and my family who were ill or had passed away. And I decided to wear a PPE mask. My dad, luckily, because of the military, had access to all kinds of masks and gloves, and he sent me a shipment. And I decided to wear one in honor of others, but also to encapsulate my own experience at home and what that was like. So I wore it while I homeschooled my children, while I did... Sorry. while I cooked and cleaned and went for a walk and played with them. And I kept the mask on for eight hours to recognize an average school day or an average work day. And I removed it every hour on the hour and photographed myself in my room and a makeshift studio. Cause that's what I had. I didn't go any place. I just went upstairs. I had the light set up. You know, I took the mask off, took two to three frames, put the mask back on and continued on my day. And, um, I did take a few pictures with my iPhone with the kids prior to starting. And they said, mommy, why are you doing this? You know? And I had to explain to them to a seven and eight year old or a six and eight year old at the time, um, you know, what I was hoping to achieve. And I think they kind of understood. And I said, people are having to wear these masks and people are getting sick. And explaining to a six and eight-year-old about a pandemic and about social distancing and about illness and about not hugging people and what they knew as life was changing faster than I could explain it or faster than they could understand. And my daughter said to me, will you be able to hug me forever? And I said, yes, as long as I'm able. But that's where the title came from because she saw what was happening as much as she could understand. And I didn't know what I was going to title the piece until she said that. And then I made these pictures. And during the process of making the pictures, I mean, my face hurt so incredibly bad and the pressure built and I started to cry. And I was able to document it all, which was really... exciting for me as a photographer, as a performance artist to have this really authentic expression of that experience. And again, I didn't know if anyone was going to see it. It was just something I needed to do for myself as a record of this time. And if I've learned anything, photography is such a great means to record your life and to allow you to reflect back on it, if for no other reason than for your own personal understanding of your journey. And here I was doing this to, you know, really for me. And then I saw the images. How did you feel? Well, like most of us in this lockdown, you know, not dying our hair or, you know, doing sort of like outlandish things that we would never do. You know, I shaved the underside of my hair and, you know, so I felt like I was in Mad Max, which, you know, in a strange way is 2021. Oh my God. Yes, it is. It

SPEAKER_01:is. Oh my gosh.

SPEAKER_00:So I felt like, I felt almost like, a warrior, right? I was a warrior, but I was a warrior at home. And so I had this undercut. And so I remember looking in the mirror that morning going, okay, I'm going to do this performance. I'm dedicating the next eight and something hours to this piece. What do I want to look like? And And so I pinned up... I had a few bobby pins in my house and I pinned up my hair so that you can see the undercut. And I knew I wanted to be nude. Although you don't see that I'm necessarily nude, but I'm nude in the pictures. And because I wanted to have nothing distracting from the marks on my face. That's what I wanted to be the central focus. And so that's the only alteration I made was pinning my hair back. And... Yeah, when I saw the image, the only time I turned sideways was at hour seven. So hour six, I'm crying. So at hour seven, I knew I had one hour left for the performance, right? I could feel the light at the end of the tunnel, so to speak. And I was like, okay, I've powered through. I have cried. I have ached. I have mourned. I have grieved. I have held it together. somewhat. I have been responsible during the day. The children are being fed. They're doing their homework and I'm cooking and cleaning and doing all the normal things. I'm doing the best I can. And so I think in hour seven, I turned sideways, sort of like a profile shot. And I feel very empowered in that picture. It

SPEAKER_02:shows. It was a powerful image. That was one that really struck me.

SPEAKER_00:Again, institutions like the Center for Fine Art Photography in Colorado and a couple other places around the country, a filter photo. We're looking for images from people responding to the pandemic. And I started sending it out. I started sending 60 pounds of pressure and I started sending, will you hug me forever? And it got picked up and people liked it and it had a really great response. And I said, oh, this is not just a record. This is something that speaks to, you know, speaks to other people and speaks to them on multiple levels and has an impact and a life after the pandemic, at least I hope so. This fall, I was very pleased to hear from the Blaffer Museum, the curators that they wanted to include it in the exhibition. And so it's on view for one more week and I hope people can catch it.

SPEAKER_02:You mentioned that there's going to be a round table discussion. Is that the one with the blacks? Monday at six. So Monday, March 8th, 6 p.m. Central Time. Yes.

SPEAKER_00:And that's all, that's almost all the artists are participating. It's not just me, but it's a round table with most of the artists in the exhibition.

SPEAKER_02:You have an exhibition on view right now in San Antonio at the Deucem Museum. You were recognized and honored to be the 2020 Artist-in-Residence. And because of the pandemic, normally you would have your solo show, but you've been paired and your work really naturally flowed in with the show they have up as well. Their show is called Beautiful Minds, Dyslexia and the Creative Advantage. However, your installation is, again, part of your Artist-in-Residency is called The Reading Brain. And I really would like to talk about that. And hopefully, again, myself Since I am driving distance, I'd like to see it. And I'm glad it's going to be on view through March 31st. Can you talk to us about the reading brain? And of course, this is on your website as well. But I wanted to hear some thought, your thoughts behind its creation and your and why you decided to do this.

SPEAKER_00:Timing. In January, I decided, well, actually, December, I decided to leave my position at Texas Photographic Society. and leave arts administration and focus on my art career. I felt it was time. I'd been pursuing it for so long and trying to really push to be an artist. And then, of course, COVID hits. I launched this huge installation or huge solo show in Austin, and then the pandemic hits. And so, like everyone, we shifted and we tried to realign our expectations. And I knew about the Dozeum's Artist in Residency program. It was a new museum that was starting to be built when I left San Antonio. And I had followed their trajectory and also followed their Artist in Residency program because their previous artists were friends of mine from San Antonio. And I had it on my calendar. I looked it up this year or in 2020. And it was right May, I think May was about the deadline. And because I was working from home or trying to work from home and homeschooling my children, I had the opportunity to apply for it. And I feel very fortunate that that came about and I saw it and I had the time to dedicate to an application. And I had never made anything, no work about dyslexia when I put my proposal together. However, my son is dyslexic, August. whose birthday is today. And I really had a clear understanding of what that challenge looked like from homeschooling him. So I knew he had challenges at school. I had spoken to his teachers. He had accommodations. You know, some days were better than others. He was struggling to read. You know, all dyslexics are not the same. There's a spectrum. But it was really during this, you know, spring term 2020 that I got to see firsthand on a day-to-day, hour-by-hour, what that looked like for him and what it meant for me. And so as I'm researching dyslexia and trying to figure out what am I going to propose to this call, and I knew it needed to be good because I wasn't based in San Antonio any longer, although I had roots to San Antonio, and so I really needed to shine and And I propose collecting data on dyslexic children and creating an interactive installation. I thought about my son and what he'd like to do. And he likes to build sculptures. And prior to the pandemic, he was taking sculpture classes at the Glassell and he loved it. And thinking about what made him happy, what he enjoyed doing. And so just going off those two things, homeschooling him and what was in his world as far as art was concerned. And that's where the idea came from. And I had originally proposed in my application working with a certain device to collect the data, which wasn't... I was asked to revise that vision. And so I made a cold call to Dr. Guinevere Eden at Georgetown University and said... I'm a finalist for this opportunity at a children's museum in San Antonio. I've worked with data before. Here's the work that I did with Memorial Herman and Point of Origin. This is why I'm doing it, because of my son. I want everyone to be excited about their brain, whether they're dyslexic or not. I want them to see that it's beautiful, that it lights up, that it works, and that it's unique, that every brain is unique, no matter how it's made. And she... wholeheartedly jumped in. And now we are friends and we keep in touch. And we had many conversations about what type of data she could share with me, how much of it, how I could use it. And then I met with a programmer here in Houston to talk about what I wanted to do and said, is this possible? Because I wasn't sure at that point what was possible. The only data-driven kinetic works... light works I had made were one piece in the Point of Origin show, which is called Life Support, which I had made for the show last year in March. And that was sort of the furthest I had gone with working with all those materials and technologies. And so I was very lucky to get connected with Clint Allen here with New Aspect Design in Houston. And he just supported me And, um, you know, we made a really great team and I'm so glad to have had him. And, um... the piece came out exactly as I intended. So I was really, really happy to see it all come to fruition and it be as engaging as I had hoped it to be. And even during a pandemic that it's interactive and children can learn and parents can learn about the different regions of the brain through these really colorful floor pattern, floor decals that tell you which region of the brain you're in and they decipher for you or decode for you how that part of the brain process language. And so one of my favorite activities that both my kids do at their Montessori school is a workbook called Explode the Code, right? And you have to figure out how to put images to text and decipher different words. And so a lot of things about dyslexia are about decoding and deciphering. And so I wanted somehow that decoding aspect of reading to be folded into the exhibition. And so the floor... the floor stickers or floor decals decode for you how the brain processes language. And so without having to touch anything, you can jump around underneath the installation. You can watch it from the outside and it'll flicker. And what it's running is six children with dyslexia and it's showing you three regions of their left hemisphere and three regions of their right hemisphere and the activation in those regions. So it'll be one child at a time and it's 84 points of data per child. over six regions of their brain, and then it'll go to the next child, and then it's on a loop. And if you enter into the installation or just walk underneath it, you will speed up the data. And if you have three children or three bodies in one hemisphere, you will speed up the data even further and shift the color palette to more saturated. And then if all regions of the brain or installation are activated, it will go to red, which in the MRI scans that Dr. Guinevere-Eden is doing, when it's red, that means full activation. So again, I was trying to connect to the scientific terminology and the scientific coding that they're doing, but also make it digestible and playful and engaging for for my children and your children and anyone's children.

SPEAKER_02:I love this. And again, just you have the installation shots and a video on your website. And that website is Sarah Sudhoff. It's S-A-R-A-H. Make sure your Sarah has an H in it. S-U-D-H-O-F-F.com. And the Reading Brain, you'll see the installation and the video on her website. I think this is a good... place for us to wrap up our conversation and let let me just say that the museum had the right title for their exhibition because it's actually i think my new nickname for you which is beautiful mind because you're beautiful inside and out but you have this amazing um Beautiful Mind. So thank you, Sarah. I really thank you for your friendship. Thank you for your talents and for so honestly and openly sharing them with all of us. I really appreciate it. So just a couple of things. The Deucem in San Antonio has, you can go and see it live through March 31st. And again, it's in conjunction with the exhibition, Beautiful Minds, Dyslexia and the Creative Advantage and the Reading Brain is what Sarah conceived and put together. Their website is www.duseum.org. And that's T-H-E-D-O-S-E-U-M.org. And at the Bluffer Art Museum, you can see Sarah's work, Will You Hug Me Forever? And 60 Pounds of Pressure. And that Will You Hug Me Forever? Just Hour 7 is on view. No,

SPEAKER_00:actually nine prints. Yeah. Nine

SPEAKER_02:prints and also a video of the

SPEAKER_00:duration. Okay. Yeah. Five minutes. Yeah. Five minute video of the 30 minute performance.

SPEAKER_02:And also for 60 pounds of pressure. So those are on view to see in person on through March 14th. And please save the date for this Monday, March 8th. at 6 p.m. I'm sure that they're going to actually keep that archival. So if you do miss it, but it'd be great to have it live because I'm sure you'll be able to ask Sarah questions. It's an online roundtable on Monday, March 8th at 6 p.m. Central. Check her website for the Zoom link or visit the Blaffer Art Museum's website at blafferartmuseum.org. And again, follow Sarah on Instagram, just her name, Sarah, Sarah with an H, S-U-D-H, And I am just so excited. Thank you so much for your time. And I know you're off to celebrate your son's birthday today. And I'm just I'm thrilled. So thank you so much.

SPEAKER_00:Thank you so much, Melissa. I really appreciate it.

SPEAKER_03:Thank you. Thank you.